Article by:

Craig Smith

— Feb 17 2019

Article by:

Craig Smith

— Feb 17 2019

Travel in Time with The Golden Era Library

Last August, I completed the preservation of 1,233 vintage optical sound effects from various Hollywood productions ranging from the 1930s to 1950s. This is the first part of a larger project I’ve been working on for nearly three years. This collection contains many sounds that give us clues about how sound effects were created during the “golden era”.

Here is the story of where these sounds came from:

In early 2016, I was working on an experimental western using B-roll found footage from the 1940 film Arizona. This involved my creating a new soundtrack that would sound like it also was from 1940. My intent was to create a layered track using newer commercial sound effects, then “age” it with digital processing.

But it sounded entirely wrong. No matter how much noise and distortion I added, it sounded too close and present, and did not “stick” to the image. It seemed something was wrong with the the sounds I was selecting. I had to rethink my methods. After studying the few vintage sound effects I could find, I realized what the problem was.

Until the mid 1950s, there were two ways to record sounds: on a phonograph disk, or on a 35mm optical film track. Since you can’t edit a record, film sound was nearly always recorded onto film. The recorders looked like motion picture camera without lenses. The signal from the microphone was used to modulate a light beam which was then was exposed on the edge of the film. The film was then developed at the lab, and copies of it were made for the sound editors. These sounds were hand edited into several “tracks” that would be used for the final mix.

The quality of these original recordings was actually quite good. The reason these old effects sound different from our new ones is that they were recorded using a different philosophy of where the mic should be, and how much sound should be recorded at once. For one thing, sound designers were limited in the number of tracks they could create for a mix. It’s common now to have hundreds of tracks playing back from a computer. But back then, every track had to be threaded onto a large machine called “dubber”. Most films probably didn’t use more than a dozen tracks. If you had 12 tracks, you needed 12 dubbers.

Therefore, the recordings were more inclusive. If we build a western street scene now, we generally add every sonic element individually. Back then, they would stage the whole scene with people walking, chattering, horse footsteps, wagons, etc. Then record it with one microphone. All of it was staged in a way that would support the image, and fit in with whatever sync sound that had been captured during photography.

As for indoor effects, they were usually recorded in large, somewhat reverberant rooms, as opposed to the small, dry, quiet foley stages that are common now. Once again, perspective was created while recording. The microphone was moved away from the source to create the desired balance between direct and reflected sound.

After realizing that I was using the wrong sounds, I got to work trying to find the right ones. I contacted several film archives, expecting them to have vast collections of studio sound effects. To my surprise, they didn’t. It turns out the studios didn’t really value their sound effects, and the rolls of optical film sound generally were taken by the sound editors as they moved from job to job. Editors shared and traded sounds with their friends, much like what we do with Freesound.org.

The last place I tried was the USC Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive. I went to the USC film school in the 1970s, and remembered there were a lot of old noisy effects in the Sound Department. Archivist Dino Everett told me that yes, they did still have those effects, but they were about to throw them out. Did I want them? Yes!

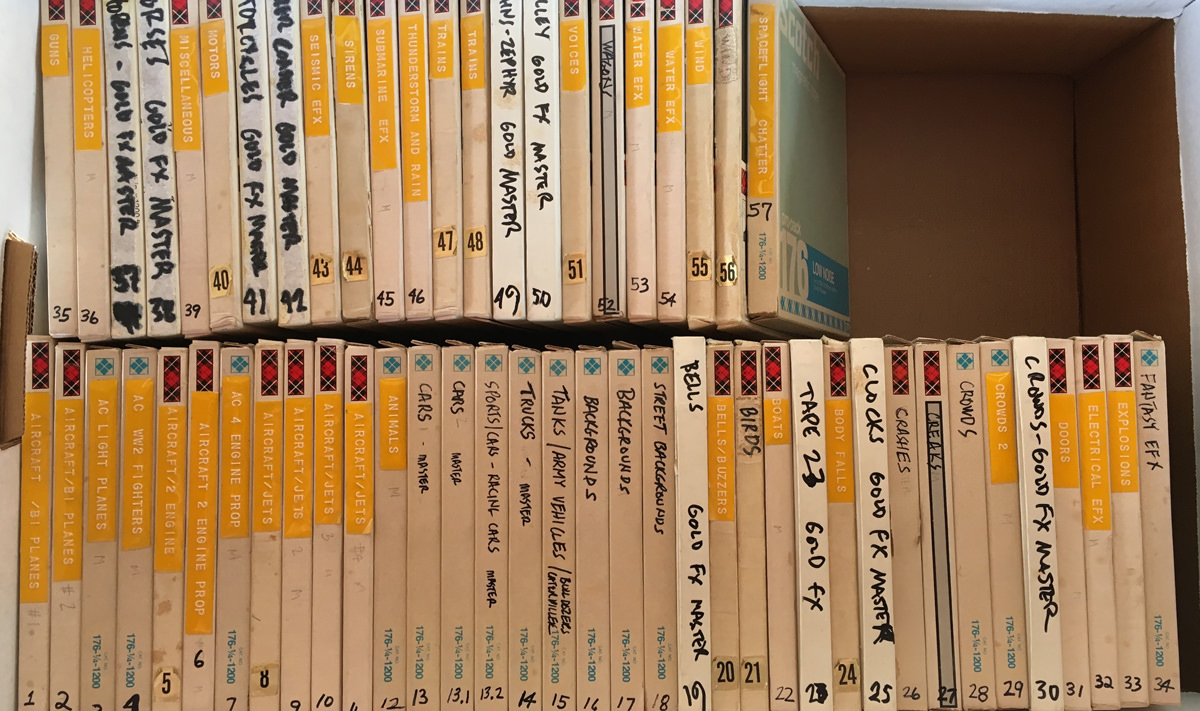

Not knowing what I was getting into, I went to USC and picked up 12 bankers boxes of 1/4” tapes. These tapes were first generation full-track recordings made in the early 1970s. USC Sound TAs would thread up small bits of 35mm optical film, then transfer each one to tape. Most of the tapes are in good condition, but unfortunately, most of the metadata (what the effects were and where they came from) is missing. While asking around to see if anyone might have a copy of the metadata, I found out that the Gold Library portion of the collection (the effects included in the Golden Era collection) had originally been transferred by Ben Burtt. Ben did this as a summer job while he was a USC Sound TA. Soon after graduating, Ben was hired by George Lukas to design sounds for the first Star Wars film.

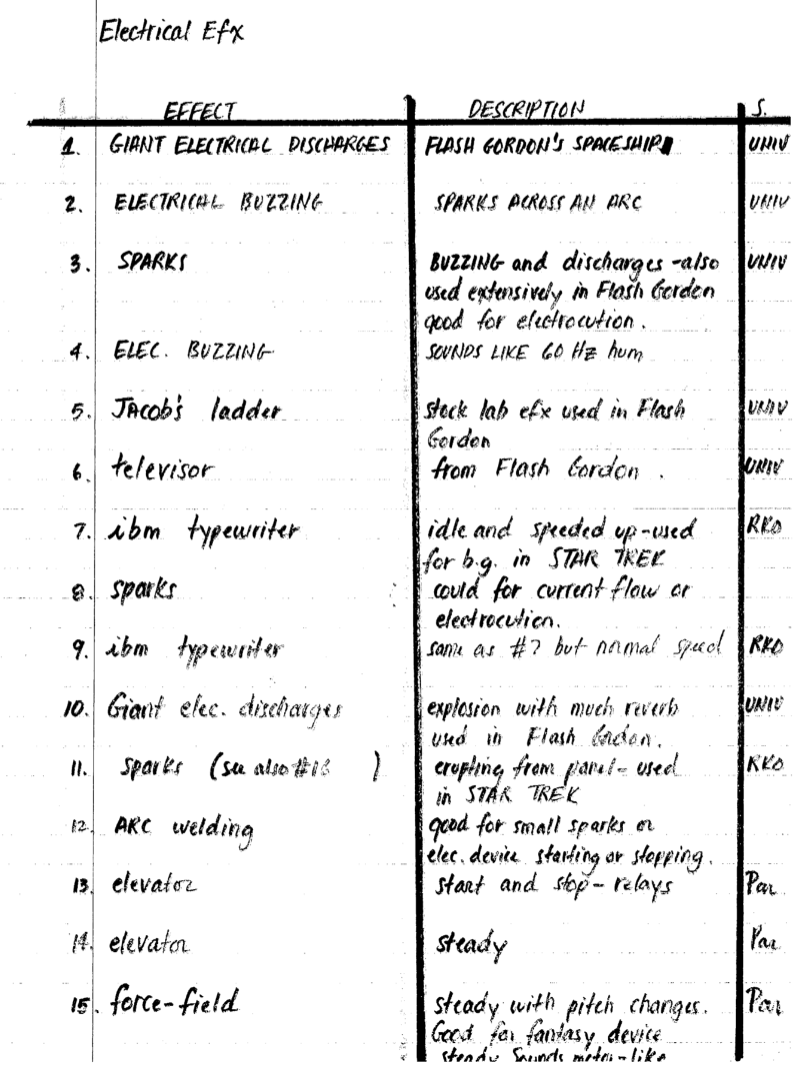

I contacted Ben and discovered that he still had his hand-written notes from when he did all those transfers! (Moral: Never throw anything away.) Ben generously made me a copy of these notes, and I was ready to start.

Except, of course, I had no idea how much time it would take to transfer, edit, and label all these effects. I do have a full-time job, and a family, so it hasn’t been easy. The tapes were transferred from a Nagra IV-L recorder into Pro Tools at 96 kHz, 32-bit floating point. They were then separated into individual files, and individual effects were level adjusted to -24 dB LKFS.

Typing in all that metadata was the biggest hurdle. After much effort, I received two grants From California Institute of the Arts that allowed me to hire an assistant and buy supplies. And Soundly gave a very generous in-kind grant of cloud space, and their software, which was used to create and manage the metadata. (I have not found a better program than Soundly for managing metadata. And the options for importing and exporting metadata are excellent.)

It’s worth noting that these effects have been preserved, but not restored. No noise reduction has been applied to them. Since these are vintage recordings, I feel there are times when some noise may be appropriate for your uses. That said, the majority of the effects sound quite good as they are. This is how they sounded during the Golden Era.

I am extremely happy that Soundly has decided to offer these Golden Era effects to Soundly users! The next installment, the Red Library, will hopefully be completed next summer. My aim in all this is to make sure these sound effects don’t disappear again. So keep using them, and keep sharing them!

I couldn’t have done this my self. I want to thank Dino Everett, Ben Burtt, Leanna Kaiser, Randy Haberkamp, Andrew Kim, Peder Jørgensen, Christian Schaanning, Frederic Font, and Lynn Becker.

—Craig Smith

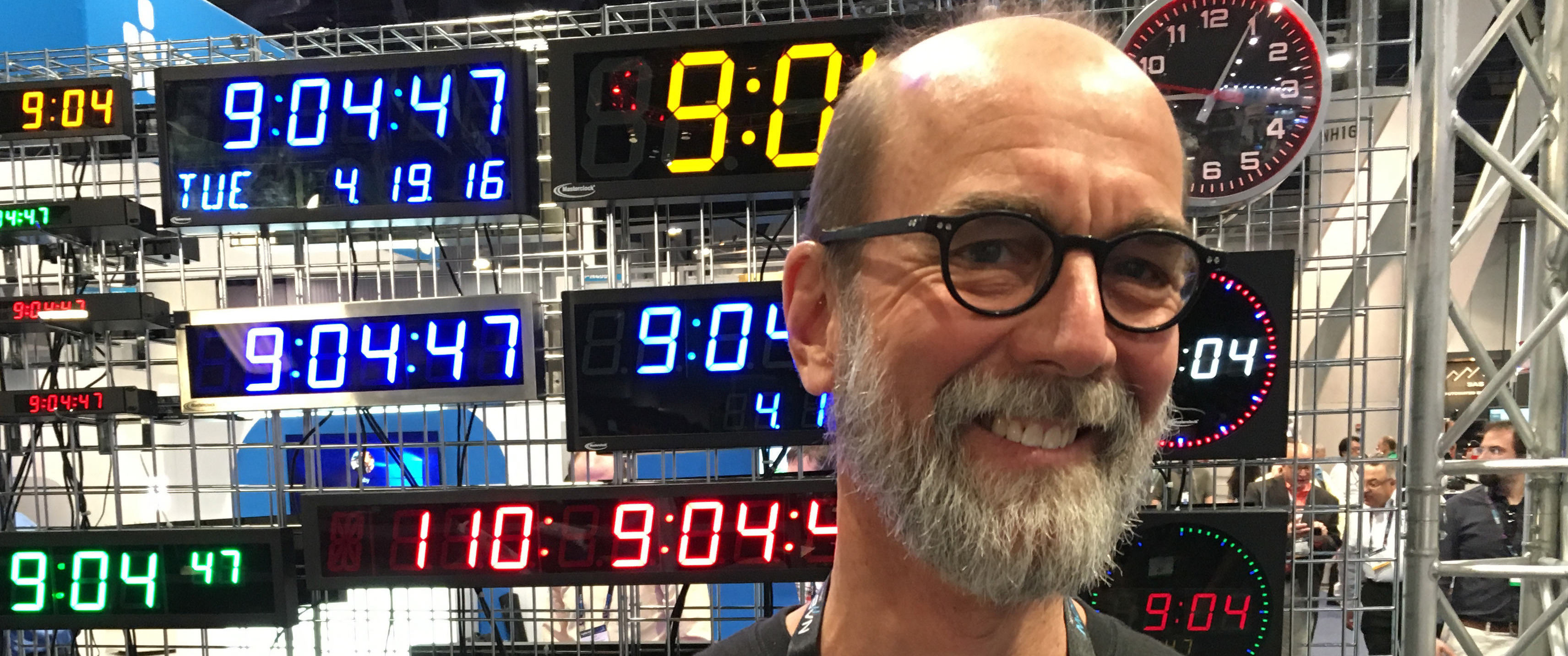

Craig Smith’s Biography

Craig Smith has been recording and manipulating sound since 1964. After graduating from USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, he worked as a sound editor and production mixer in Hollywood, specializing in noisy action-adventure films that are blamed for the downfall of society. He left that world in 1986 to teach at California Institute of the Arts, where he is now Academic Sound Coordinator in the School of Film/Video.

Craig’s own work experiments with implied narrative and accidental sound design – putting together sounds & images that have nothing to do with each other to create unexpected stories.

Craig is a member of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, and the Audio Engineering Society.

To get The Golden Era Library, go to the store inside Soundly, and add it for free.

Download Soundly at getsoundly.com